The EU and Britain have met resistance to a new $85 million project to simplify cash allowances for Syrian refugees. In future, only one contractor will handle the payments and another will monitor the project, replacing systems involving some nine aid agencies.

The donors say the new arrangement, due to start in the next few months, will reduce duplication and improve accountability. The new formula, however, challenges the humanitarian status quo. A senior UN official says it may “undermine coordination” and “create problems”. The atmosphere around the bidding process has been at times “toxic”, insiders say.

Analyst Wendy Fenton of the Overseas Development Institute described the scheme as “deliberately disruptive” and a “real departure from business as usual”. The donors argue the design was a logical outcome of reform commitments made at the World Humanitarian Summit last May and is in the best interests of refugees and taxpayers.

As IRIN has reported, the Lebanon operation is already a pioneer when it comes to using cash and bank cards to support refugees. Needy refugees get a variety of entitlements according to their circumstances, channelled as top-ups on a debit card. They also get e-vouchers to buy food. The key agencies are UNHCR, WFP and UNICEF, as well as a six-NGO group, the Lebanon Cash Consortium. Having moved the various systems to a single card and bank recently, the new proposal will simplify one channel still further.

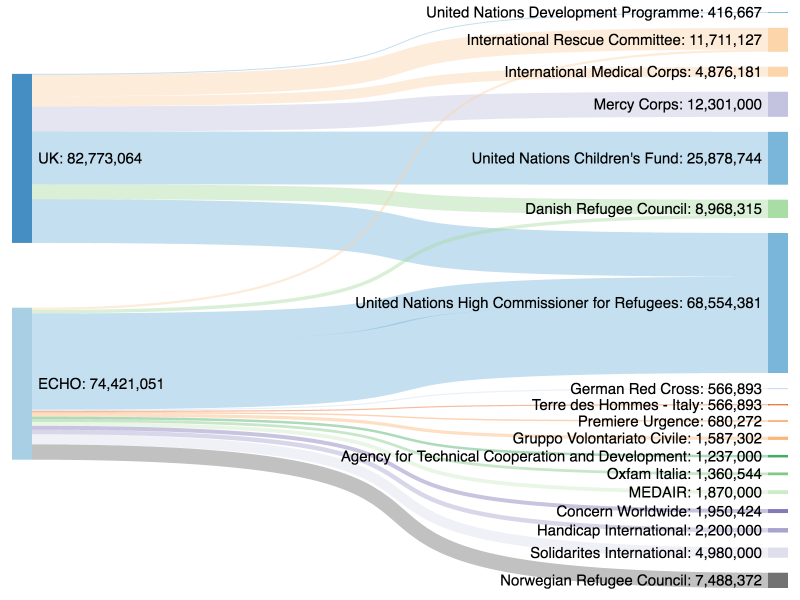

The proposition – from the EU’s humanitarian aid arm, ECHO, and Britain’s international development department, DFID – departs from the status quo in three main areas: a single agency will manage cash transfers from the two donors; a separate independent contractor will monitor; the project will insist on delivering money, instead of vouchers.

“Common sense”?

The backers say the new concept is common sense. Opponents believe the move is hurried, the benefits unproven, and that a de facto monopoly will be less effective than the status quo.

The UN’s humanitarian coordinator in Lebanon, Philippe Lazzarini, told IRIN the current system benefits from the “diversity and comparative advantage” of the variety of agencies involved. He said it represents “good practice” that “optimises and respects the respective mandates of the involved agencies”. He said those involved continue to look for further efficiency and impact gains, but “calling for a single agency provider in this context bears the risk to undermine the comprehensive coordination efforts”.

UN agencies have lobbied vigorously against the Lebanon move, sources close to the process told IRIN. Another source said that even within the UN family there were “massive disagreements”, as agencies fear the prospect of falling turnover and influence.

New research from Ukraine suggests that disputes over the management and coordination of cash-based aid is far from unique to Lebanon. In a fresh report from ODI, the risks of a muddled approach are described clearly: “Strategy and coordination became highly political, mandate-driven and largely removed from analysis on the best way to assist people. The lack of clear, global guidance on where cash transfers fit in humanitarian coordination and planning enabled agencies to contest arrangements that did not favour their institutional interests.”

A blog posting on the Cash Learning Project (CaLP) website, which included views of other critics, said: “we’ve been talking to the people involved. There is no hiding the widespread concerns.” It mentioned worries about how the transition to a new system would be handled, and how the interests of the most vulnerable refugees would be protected. It also stated, more bluntly, the fact that NGOs faced shrinkage: “NGOs now find themselves at risk of losing the footprint among communities and people in need that cash assistance has provided them for years”. More broadly, critics claim there will be a drop in quality and sophistication while the “marketplace” will become concentrated in the hands of those agencies “big enough to bid”.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license